Storyboards Workshop iSchool 2014

Written summary of a workshop given at the Faculty of Information on Storyboarding, January 2014

Storyboards started as visualization tools for animated cartoons. Communicators adopted them to plan films, and multimedia projects like DVDs, apps, and Websites. Visualizing is a skill independent of drawing skills used in the creation of storyboards that anyone can learn. If you can imagine and draw stick characters and basic shapes, then you can create storyboards.

Use storyboards as blueprints to exchange design information with other stakeholders in a project. They are the ultimate collaboration tool. Storyboards communicate visual information. As an information architect, I view storyboards as visual information architecture. Blocks of visual information arranged and shared with other users.

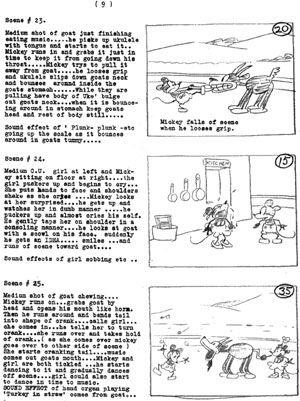

Storyboards are a form of sequential art, the underlying art form known as comics. So while storyboards are comics, they are drafts and rough documents, not polished pieces. Their form is intermediary and meant to represent another medium such as animation, film or a mobile app.

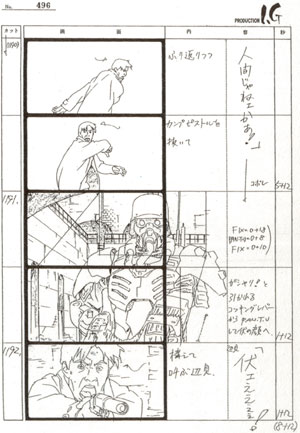

Storyboards contain two information-rich areas. One is a visual. The other is textual and conveys other forms of information such as sounds and metadata. Effective storyboards replicates information in several different format side by side, frame after frame.

Each frame represents one main event happening in the end medium. Storyboard artists draw the content of the frame and add relevant information related to the visuals. Every time something major happens in your project, you should draw a new frame. The accumulation of frames mimics what is happening on the screen through time.

Think of your storyboard as a story that you start and end. Your goal is to convey a story to the viewer. You can measure the success of your storyboard by how well people understand the information it conveys.

There is unfortunately, no magical way to get this kind of visualization skill. It is a tacit skill that you can understand only if you attempt to create storyboards. Repeat simple everyday scenes and try to sketch them out on paper as a series of drawing with basic information. The more you practice this, the better you will get at it. Storyboarding is a qualitative skill. Although you should know of a few formatting guidelines, there are no magic tricks when creating a storyboard.

Animators use storyboards in animatics. Animatics use storyboards and create cheap animations combined with soundtracks.

There are many formats to storyboards. There are also tools sold by several software vendors to help you create storyboards. I suggest relying on a blank sheet of paper and several sharpened pencils. Software can get in the way of your visualization skills. It makes you focus on a programs’ interface and its constraints, rather than on the idea that you want to illustrate. If you don’t like a drawing, just toss away the sheet and start again. Don’t dwell too long or over think a drawing. If it gets confusing, just start over on a new blank sheet of paper. That’s why I suggest that people new to storyboards don’t use erasers. Dr. Betty Edwards (1979) argued that critical thinking while drawing stops creativity. You can create a basic storyboard by taking a sheet of paper and drawing straight lines with a ruler to create your various frames. That’s all you need to start off. Every storyboard artists develop their own templates over time. All that’s needed is something that you are comfortable using.

To help your learn to storyboard, start with a simple written scenario. You’ll notice that you can translate every action into a frame.

When creating storyboards, we often need to document camera movements. You may have heard the terms “trucking, pan, zoom in, birds’ eye view, wide shot and close ups. Trained cinematographers and animators know when to use them and when to avoid them in their storytelling. These instructions should be in your storyboards. Daniel Arijn has written an excellent book titled Grammar of the Film Language. I have lent it to friends many times and lost it every time (I’m on my fourth copy). It lists every possible kind of shot and camera movement you are likely to see in an animated or live action film.

Visit the Storyboard 101 page from Toon Doctor to learn more about storyboards' history and uses. In conclusion, remember that you can only learn about storyboards through doing. That’s why I don’t recommend any text about storyboards here because there aren’t good ones. Many art books collect original storyboards from movies like The Matrix (1999) or Disney features. These are fun and inspiring to watch. But when viewing them remember that it’s not the drawing quality that makes an effective storyboard. I measure effective storyboards by how fast I understand their visual information.

Happy Drawing

Works Cited

Arijon, Daniel. Grammar of the film language. New York: Hastings House, 1976.

Edwards, Betty. Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. New York: Penguin Books, 1979.

Hervé Saint-Louis, PhD Student

Faculty of Information (iSchool)

February 4, 2014